Timely Lessons for Worker Voice Today

Earlier this year, President Obama designated the Pullman District a national monument. By celebrating this community on Chicago’s South Side, the birthplace of the nation’s first African-American labor union, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, this proclamation once again links the labor movement to the birth of America’s middle class. And it lifts up A. Philip Randolph and the Pullman porters as leaders of both our labor and civil rights movements. Secretary Perez has often noted, citing both the Memphis sanitation workers and the Selma-to-Montgomery march, the inextricable links between organizing for workers’ rights and for racial justice.

At a time of unparalleled inequality and labor-management hostility in the early 20th century, few would have predicted that the rail car company built by George Pullman — someone intractably opposed to worker self-determination — would ultimately negotiate with an African-American labor organizer and “agitator” like Randolph. And yet, ultimately, the model town built by Pullman for his workers went from being an epicenter of strife to a model for industrial peace and democratic values. It speaks to the surprising potential for redemption when bitter adversaries are able to forge new partnerships and identify mutual self-interest.

It was this transformation that President Obama honored, together with leaders from across the aisle; four congressional Republicans urged the president to take action, noting, “This unique site represents an extraordinary chapter in American history.” They added that “the ripple effects from the labor unions at the Pullman site affected not only the social fabric of our nation, but also the industrial norms,” as the porters led the fight for better wages, safety and working conditions.

The Pullman porters started off with no organizational home, no labor laws to protect them. They were former slaves whom Randolph believed could and would prevail in their quest for organization and full human dignity. It took twelve long years, but they ultimately made history by successfully forming their union in 1937. We can best honor them now by seeing them in the faces of today’s domestic workers, taxi drivers, car wash, retail and fast food workers – all of whom are developing innovative ways to assert and exercise their rights at work. This time, these workers have support from the traditional labor movement — the AFL-CIO, SEIU and others, who have welcomed and nurtured new alliances. Today, fittingly on A. Philip Randolph’s birthday, fast food workers are again raising their voices for justice on the job.

Our current challenges in the area of worker voice seem just as daunting as those that confronted Randolph and the porters nearly a century ago. Pullman was the nation’s pre-eminent industrial employer, regarded as unyielding and recalcitrant in its opposition to unions and worker voice. But change did come, and now we honor the porters’ struggle as a landmark triumph in the history of the labor and civil rights movements. And while it may take time yet for new organizational forms to emerge or labor laws to catch up to the 21st century workplace, workers in motion are already winning concrete victories:

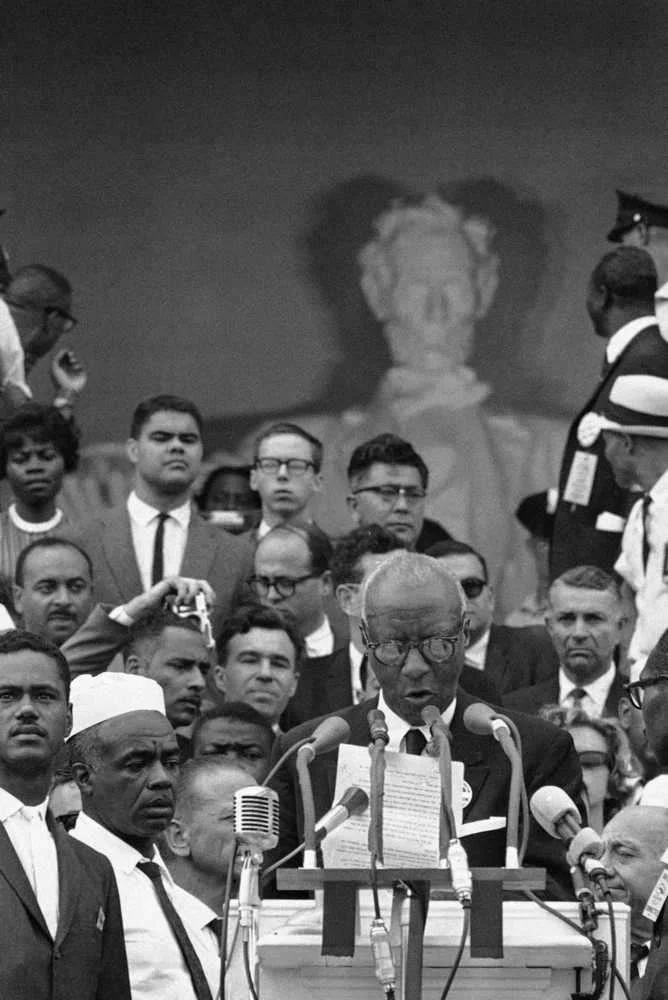

A. Philip Randolph speaks to the crowd at the March on Washington, August 28, 1963. (Credit: AP photo from Jacksonville.com)

Millions have benefited from new minimum wage and sick leave laws at the state and local level. Millions more are getting bigger paychecks, as company after company responds to the growing consensus that it’s better for all of us when workers can earn their fair share.

We are seeing a surprising pivot across the spectrum, with a new consensus emerging that the economy as a whole is strongest when workers are empowered and self-sufficient; when they can earn their share of the value they help to produce. Walmart, for example, as powerful a corporation as Pullman was a century ago, just announced a wage increase for its workers. When labor and management wrestle over their differences and negotiate in good faith, they ultimately settle on solutions that serve both the bottom line and create equity for people that produce that value.

Just like the Pullman porters, many workers today don’t have labor law on their side, but still they are finding ways to organize and take action. Randolph and the Pullman porters created something that had not yet been imagined; we may not yet be able to see exactly how new forms will emerge but change is happening. We may be entering a similar creative time with workers pursuing new organizational models that restore balance in their workplaces, and with employers responding by changing their policies in a way that benefits all stakeholders involved.

Originally published April 15, 2015.